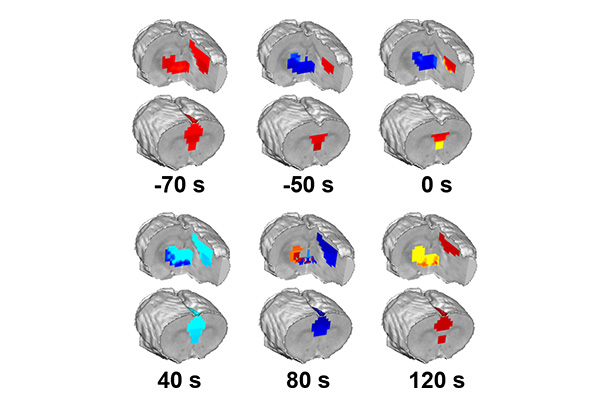

Through studies on rats, a team of researchers at Penn State has pinpointed the exact moment of loss of consciousness due to anesthesia, mapping what happens in different brain regions during that moment. Credit: Provided by Nanyin Zhang.

Brain mechanisms underpinning loss of consciousness identified

Rapid activity in three brain regions appears to trigger loss of consciousness, researchers at Penn State find

Dec 10, 2024

By Sarah Small

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — The shift from an awake state to unconsciousness is a phenomenon that has long captured the interest of scientists and philosophers alike, but how it happens has remained a mystery — until now. Through studies on rats, a team of researchers at Penn State has pinpointed the exact moment of loss of consciousness due to anesthesia, mapping what happens in different brain regions during that moment.

The study has implications for humans as well as for other types of loss of consciousness, such as sleep, the researchers said. They published their results in Advanced Science.

“People in the neuroscience field generally understand what happens to a patient who is going under anesthesia at a molecular level,” said corresponding author Nanyin Zhang, the Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Chair in Brain Imaging and professor of biomedical engineering at Penn State. “But at the so-called systems level — meaning how different brain regions or neural circuits change their function in responding to the anesthetics and loss of consciousness — it wasn’t very clear. Our study set out to address this unknown.”

To do so, the researchers combined two different methods: electrophysiology studies and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). By measuring electrophysiological signals — or electrical activity — in the brain very quickly over time, the researchers determined the precise moment that the rat transitioned from an awake state to an unconscious one.

They next overlaid this time-stamped data with the fMRI map of activity in the whole brain to investigate different regions of the brain during that transition.

“We found that there were three regions in the brain that showed transient changes in their activities during the moment of lost consciousness: the medial prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus and the thalamus,” Zhang said. “While these regions have been implicated in unconscious states in the existing scientific literature, our research was the first to indicate how these regions might interact with each other and what kind of role they might play during the moment of loss of consciousness.”

The researchers said previous work also did not indicate whether the activity in those three regions was a cause or an effect of loss of consciousness. Zhang and his team’s results suggest that loss of consciousness may be triggered by sequential events in these three regions, while activity increases in other cortical regions may be a consequence, rather than a cause, of loss of consciousness, according to Zhang.

“While the results were not necessarily surprising, they do provide new insights into the roles of these brain regions in loss of consciousness,” Zhang said.

The other authors on the paper are Xiaoai Chen, a doctoral candidate in biomedical engineering; Samuel R. Cramer, a doctoral student in the neuroscience graduate program through the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences; Dennis C.Y. Chan, a doctoral student in biomedical engineering; and Xu Han a postdoctoral fellow in biomedical engineering.

The National Institute of General Medical Sciences partially supported this work.