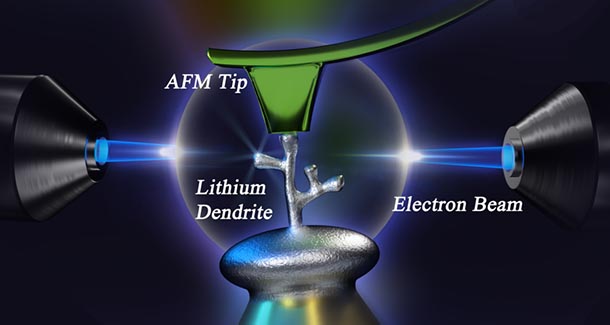

A lithium dendrite is imaged and stress-tested under an atomic force microscope tip. IMAGE: ZHANG LAB/PENN STATE

A new method to study lithium dendrites could lead to better, safer batteries

1/9/2020

By Walt Mills

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Lithium ion batteries often grow needle-like structures between electrodes that can short out the batteries and sometimes cause fires. Now, an international team of researchers has found a way to grow and observe these structures to understand ways to stop or prevent their appearance.

“It is difficult to detect the nucleation of such a whisker and observe its growth because it is tiny," said Sulin Zhang, professor of engineering science and mechanics and biomedical engineering, Penn State. "The extremely high reactivity of lithium also makes it very difficult to experimentally examine its existence and measure its properties.”

Lithium whiskers and dendrites are needle-like structures only a few hundred nanometers in thickness that can grow from the lithium electrode through either liquid or solid electrolytes toward the positive electrode, shorting out the battery and sometimes causing fire.

The collaborative team from China, Georgia Tech and Penn State successfully grew lithium whiskers inside an environmental transmission electron microscope (ETEM) using a carbon dioxide atmosphere. The reaction of carbon dioxide with lithium forms an oxide layer that helps stabilize the whiskers.

They report their results online this week in Nature Nanotechnology. The paper is “Lithium whisker growth and stress generation in an in situ atomic force microscope–environmental transmission electron microscope set-up.”

Innovatively, the team used an atomic force microscope (AFM) tip as a counter electrode and the integrated ETEM-AFM technique allows simultaneous imaging of the whisker growth and measurement of the growth stress. If the growth stress is too high, it would penetrate and fracture the solid electrolyte and allow the whiskers to continue growing and eventually short-circuit the cell.

“Now that we know the limit of the growth stress, we can engineer the solid electrolytes accordingly to prevent it,” Zhang said. Lithium metal-based all-solid-state batteries are desirable because of greater safety and higher energy density.

This new technique will be welcomed by the mechanics and electrochemistry communities and be useful in many other applications, Zhang said.

Next up for the team is to look at the dendrite as it forms against a more realistic solid-state electrolyte under TEM to see exactly what happens.

The researchers are from Yanshan University, China University of Petroleum and Xiangtan University, all in China; and Ting Zhu of Georgia Tech.

The National Key Research and Development Program of China, Beijing Natural Science Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and several additional Chinese foundations, supported this research.