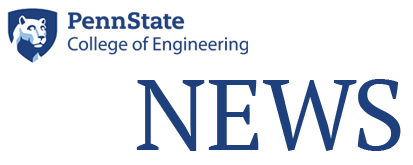

Deb Kelly, right, and members of her research team analyze breast cancer data at Penn State’ Center for Structural Oncology. IMAGE: JAMIE OBERDICK

Discovering the secret life of cancer cells

1/20/2020

By Karen Walker, Town & Gown magazine

When a Penn State sports team lands a big recruit or hires a new head coach, it’s often front page news. Press conferences are held, and fans and sports analysts take to social media and news outlets to discuss the individual’s potential impact on the team’s future. But one year ago, Penn State signed one of its biggest superstars to date, and, although the impact she and her team are making could potentially be life-changing for millions of people, chances are you haven’t heard about her — yet.

She is Dr. Deb Kelly, professor of biomedical engineering, Lloyd & Dorothy Foehr Huck Chair in Regenerative Engineering and director of Penn State’s new Center for Structural Oncology, and she and her 12-person team have made some groundbreaking discoveries regarding the gene mutations that cause cancer. A pioneer in this type of research, Kelly coined the term “structural oncology” to reflect the center’s emphasis on studying the structure of cancer cells.

“It simply but elegantly describes what we’re doing,” she says. “I always say that we look at small things in a big way. We try to understand the molecular culprits of breast cancer, and how those cause the disease to spread throughout the body, through a new set of eyes.”

That new set of eyes is supplied by the multi-million dollar, high-powered microscopes housed in the Kelly Lab in the basement of the Millennium Science Complex on the University Park campus.

“It’s a huge array of instruments that are really diving into the secret life of cancer cells in a way that no one has seen before,” she says.

In fact, using those microscopes, Kelly and her team members became the first people in history to see the molecular protein mutations that appear to be at the root of both breast cancer (BRCA1) and pancreatic cancer (P53).

“BRCA1 is a gene found in every cell in your body,” she explains. “Its job is actually to protect your cells from cancer forming. But if something goes wrong with that gene, we know that there’s a 50-50 chance that you’re going to end up with cancer in your life.”

Those odds are not precise enough for Kelly’s liking.

“When you think about it, 50-50 is like a flip of a coin. Not all women with mutations end up getting breast cancer, and some women without mutations in these genes get breast cancer. So, what’s really going on? What’s the tipping point?” she says. “If we can find the root cause of these invasive breast cancers and better understand causes and predictive measures, we can try to make a difference in people’s lives. So we work on the proteins in high detail to understand how cancer forms and does not form inside women’s bodies.”

Kelly and her team discovered that the BRCA1 protein is shaped roughly like a letter “C” and the mutated version sprouts little tags that cause it to work improperly. She describes seeing this for the first time as a “eureka” moment.

“It’s very exciting at that moment, but a few minutes later, you kind of shift to, ‘Wait, that little smidge of a protein that is misbehaving is what is causing all those problems in people? Why? What can we do to fix this? How can we combat it better?” she says.

On that front, Kelly’s team has made exciting progress. They have identified ways to make mutated BRCA1 proteins work like normal genes should, at least in a lab setting. Now Kelly is hoping to take this research to the next level and test it on human patients.

“It’s a question of how can we tweak the system for success rather than for disease. Our body naturally has all the right tools inside, so when cells are misbehaving, you just have to redirect them, just like when a child is misbehaving …. That looks like it’s going to be successful from what our early data would indicate.”

Kelly has a background in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), molecular biophysics, chemistry, and biotechnology, and came to Penn State after eight years at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, relocating most of her research team to State College in January of 2019.

“We are loving the Happy Valley area … Penn State has even better tools and resources and ways in which we can look at these proteins that we never had the opportunity to do before. In the less than a year that we’ve been here, I transferred my entire research portfolio here, and almost $7 million in funding from the National Cancer Institute. We’ve published five additional papers and received three additional new grants,” she says. “It’s really taken off here at Penn State.”

Kelly is not the kind of scientist to keep her research results confined to the walls of her lab. She collaborates with pharmaceutical companies and cancer foundations to work toward developing practical interventions for cancer patients, and she is especially interested in community outreach.

“I’m a researcher that likes to go out and interact with the public and talk with survivors. I’m particularly interested in establishing ties with women who have been diagnosed with these genetic mutations and don’t know what to do,” she says. “I think there should be support groups for people with the BRCA1 mutation — a place to share information in a hopeful way.”

Kelly is a “research ambassador” for the Pink Zone, working to spread a message of hope about cancer research findings via social media (@DebKellyLab on Twitter) and other means. She also serves as program leader for the Penn State Cancer Institute’s “Next Generation Therapies,” a collaboration between different research groups that looks at ways new discoveries can be used to help Pennsylvania cancer patients. She is disheartened but driven by Department of Health statistics that indicate that invasive breast cancer has overtaken lung cancer as the top cancer diagnosed in Pennsylvania women, and that cancer is eclipsing heart disease as the number one killer for adults aged 45-64 in developed countries.

“You think we’re getting better at this, and we have made great strides, but I think what needs to happen is something similar to what the science and research community got together to do to combat HIV. Everyone went all-in on HIV and developed all these new drugs and new ways of combining drugs and thinking about it. Now, if you get an HIV diagnosis, you go on drugs and can live a normal lifespan at a healthier degree. If we can just do that with cancer, it would be huge.

“We have to do better. These are the things that keep me up at night.”

Still, Kelly seems optimistic about what lies ahead.

“We are going to be making a lot of forthcoming discoveries out of Penn State, hopefully in the next six months. I think the opportunities are limitless for me and my team,” she says. “As technology and computing power improves, so do all disciplines of science and medicine. When you look at where we were 10 years ago and how far we have come, I imagine within the next decade we are going to see a lot of wonderful things. I expect a lot out of my team here at Penn State to really put us on the map in our new location.”

This article originally appeared in Town & Gown magazine’s Pink Zone 2020 issue.